According to a WSJ article today (12/11/2007, B11, "Age of Innocence") there is a severe consequence to watching tv and browsing the internet to the exclusion of reading. Reading gives pause -- time to reflect -- not just react. Of course the report was from the softest of scientific sectors, sociology, but Caleb Crain is a name with a nice ring, and he did cite the National Endowment for the Arts. And what am I doing? Who is my audience here? Internet browsers or bookstore browsers? The answer is that probably no one is reading this. But the only way you can find this is on the Web. And you have to read to get here.

The other interesting correlation that Crain makes (or the report he is reading, makes) is that readers are "more likely to exercise, visit museums, ..." But the most important connection is that readers are more open-minded than non-readers. hmmmm. Now that's important in a democracy, in an election year, no less. That would make You Tube members (Watch it. If I am assuming they surf more than read, and I am the Walrus (and really enjoy You Tube), I need to read a membership profile before I speak and join hands with the shallow and closed-minded and start making opinions facts.) closed-minded and Time Magazine readers the people I want to talk to (to is okay at the end of the sentence according to the rules of New English -- Fowler has been trumped).

One other thought -- do you read me?

This blog began as an educational project created in partial fulfillment of a grade for 610:510 at SCILS at Rutgers University, along with responses to readings about humans gathering information and the studies that have been done. There are also jottings and links to major journals or articles or current feed to good literature and relevant writing today.

Wednesday, December 19, 2007

Saturday, November 17, 2007

Kimbel and Cabus -- Cabinetmakers of Curiosity

Here is a draft which will be edited over the next few weeks, right here.

Introduction

Anthony Kimbel and Joseph Cabus were names associated with fine cabinet making[1] in late nineteenth-century New York City where many other European-influenced firms also thrived in the industrious world of the furniture arts on Lower Broadway. Gustave and Christian Herter arrived in 1848. Edward W. Hutchings (1836-1856), Alexander Roux (1837-1881), Auguste Pottier (1823-1896) worked in the same neighborhood. The luxury hardware business of P.E. Guerin was founded on Jane Street in 1864.[2] While the names Kimbel and Cabus were spoken together in the same company as Herter and Roux, and they shared clientele with prominent architects like Stanford White, it is baffling that to date, other than a sole trade catalogue, ostensibly no invoices or other business records have been left behind. In spite of this, examples of Kimbel & Cabus furniture turn up in the Cooper-Hewitt, the Brooklyn Museum, the Hudson River Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and other public collections. There are also surviving examples in the US Capitol, Henry Ford Museum, and the High Museum of Art. Today Kimbel & Cabus are best remembered for having created and introduced the American version of Gothic Revival[3] style to a very receptive public at the Philadelphia Centennial in 1876.

Kimbel and Cabus [biographical details]

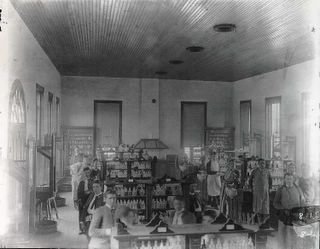

Between 1863 and 1882 in the Madison Square Park area of the City of New York, Anthony Kimbel and Joseph Cabus operated their fine cabinet making[4] ,decorating shop and showroom in the heart of the burgeoning retail district where R.H. Macy, B. Altman, and Lord & Taylor had already established themselves. [5] Their trade card read, “Kimbel and Cabus, Cabinet Makers and Decorators”, and paper labels with the same logo identified their wares.

Anthony Kimbel and Joseph Cabus moved many times during their close to twenty-year partnership, achieving some prosperity, but spent their peak years at 7 East 20th Street, and 458 10th Avenue. The firm achieved a reputation for high quality design and manufacture of furniture in a variety of styles, but gained prominence in the 1870s for developing an American version of Gothic Revival[6] or Modern Gothic style furniture featured in the trade catalogue dating from this period. [INSERT FIGURE]

Anthony Kimbel’s earliest training as a cabinet-maker was under the tutelage of his father Wilhelm (1786-1869), a master craftsman in Europe, and his godfather Anton Bembe (1799-1861), a furniture dealer and decorator in Mainz, Germany. He continued his education in Paris working with furniture maker Alexandre-Georges Fourdinois and publisher Desire Guilmard before coming to New York in 1847. In New York, Kimbel became the principal designer in the shop of Charles Baudouine and in 1854 established the firm of Kimbel & Bembe with the backing of his German uncle, Anton Bembe. Kimbel’s knowledge of European ornament and style (notably Rococo-Revival) and his ability to produce quality pieces for an American market enabled the firm of Kimbel & Bembe to flourish.

Joseph Cabus came from a family of French-born cabinet makers who had established a furniture manufacturing business in New York in the 1830s. As a boy, Joseph worked with his father Claude and then trained with the prominent cabinetmaker Alexander Roux in the 1850s before opening his own workshop at 924 Broadway, in 1862. Just a year later, Kimbel & Cabus would open, next door at 928. There in the years following the Civil War Kimbel & Cabus’s factory and showroom expanded greatly, allowing them to move to a quite fashionable site at 7& 9 East 20th Street by 1873[bey1] . In 1876, Kimbel and Cabus had developed a distinctive enough style of Modern Gothic at the Centennial in Philadelphia for their booth (#327) to be considered “rich and tasteful enough to rank among the very best of American exhibits in household art.” (Voorsanger, Encyclopedia of Interior Design). [INSERT FIGURE OF CENTENNIAL BOOTH]. At the height of their careers then, they were listed as exhibitors in the Official Catalogue of the 1876 International Exhibition in the Main Building’s Department of Manufactures with others — Brown & Bliss (#340), the Kilian Brothers (#338), Daniel Pabst (#361) , and Pottier & Stymus (#373), whose cabinets were similar in design to their own, and sometimes even mistaken for them.

Later commissions included the woodwork interiors and furniture for the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church (1875) and the interiors for a Company Room at the Seventh Avenue Regiment Armory (1879-1880). After Kimbel & Cabus closed their doors in 1882, both Anthony Kimbel and Joseph Cabus continued to work in partnership with their sons. A. Kimbel & Sons was more successful than Kimbel and Cabus and remained in business until 1941.

On his own, Joseph Cabus rose to prominence as a cabinet maker, but it was not until after the dissolution of the Kimbel and Cabus partnership that he landed his most famous commission in building the interior of the Church of the Ascension on lower Fifth Avenue in New York in collaboration with Stanford White in 1884.

Keeping Up Appearances: The new middle-class in late 19th century America

Victorian culture was the first to use the safety pin (1849), the typewriter (1867), the telephone (1875), and the first to profit from balloon frame construction (1832), a popular and inexpensive building technique that allowed people with modest incomes to afford to purchase homes. The mid- to late-nineteenth century in New York alone saw the rise of the first modern hotel (The Astor, 1830s), the first department store (A.T. Stewart Dry Goods, 1846), and the first chain grocery store (New York-based Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, 1864). Nearly six thousand newspapers and magazines were being published in the United States by 1870, with 1.5 million copies issued annually. A large percentage of these publications instructed the new middle class in etiquette, health, home decoration, gardening, hygiene, and taste. Its members developed a taste for the “new” as a way of “keeping up appearances,” which was not easy at a time when the most idiosyncratic and eclectic designs dominated the culture, especially the decorative arts. A young middle class was beginning to acquire decorative objects, the objects they saw at international fairs and in the lavishly illustrated magazines whose woodcuts they pored over. As long as the new middle class was able to imitate something that pleased their senses and be affiliated with the avant-garde, the demand for novelty would flourish. By 1877, Thorstein Veblen had coined the term conspicuous consumption to describe the drive to show off what you own to your friends and neighbors.

The furniture trades in New York City were thriving. Of the 4.2 million foreigners entering the United States between 1861 and 1877, most came ashore in New York City and would stay there. By 1870, New York was the busiest American seaport and the major distribution and sales center for imported goods in the country. At the same time, a number of skilled craftsmen and artisans arrived from Europe bringing with them both traditional and avant-garde designs which American firms quickly adopted, manufactured and marketed. The confluences of prosperity, technological and industrial innovation as well as the advent of mass merchandising provided opportunities for middle-class consumers to attain home ownership. These Victorians were the first ‘‘consumers” of mass-produced luxury items, made suddenly available to middle-class and wealthy households as one of the benefits of industrialization. As the economy expanded, the new middle class tastefully furnished their new residences with the latest styles and textiles of the day. Idiosyncratic and eclectic designs and products dominated the culture in the decorative arts.

The success of furniture manufacturing and interior furnishing firms such as Kimbel & Cabus was due to the patronage of this young, educated middle-class consumer who had developed a taste for the “new” as a way of “keeping up appearances.” New ideas and trends in etiquette, health, home decoration, gardening, hygiene, and taste, eagerly sought out by middle-class readers, became regular features in the nearly six-thousand newspapers and magazines being published in the United States by 1870. Illustrated serials and mail order catalogues fueled the desire to obtain fashionable decorative household objects as did the publication of a number of popular home decorating manuals. An abundance of popular magazines and manuals of instruction brought the great halls of the wealthy right to the parlors of the reading public. The Ladies Home Journal (first published in 1883), Cosmopolitan (1886) and Vogue (1892) raised the level of expectation for the burgeoning middle class.

How-to books like A.J. Downing’s The Architecture of Country Houses went through nine printings between 1850 and the end of the Civil War. Downing’s choice of furnishings for his audience did much to prescribe the types of furnishings that the new homeowner should choose in establishing an ideal American way of life and emphasizing the practice of attaining prestige. He did much to establish the understanding of the picturesque as beautiful and the unity of design as a form of truth and high morals. In the history of taste, it must be considered one of the nineteenth century’s best “how-to” manuals as well as a primer of the aesthetic interior and its accompanying manners and values.

The opportunity to own a home became affordable with the rise of mass culture, and with the rage for home ownership and the proliferation of the middle classes, the stage was set for craftsmen to sell their wares to a new market. The Victorians were the first “customers” of mass industry, and they wanted whatever elevated their status. The home was the ideal place to display status. The neo-Gothic with its underlying accent on perfection was just the right line of products to pitch to the first mass consumers, who yearned to have the pleasures of the wealthy. With their linearity and pointed features, Kimbel & Cabus’s furnishings offered the connection between the Gothic and good character that Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin established in England through writings that influenced Bruce Talbert and others. With their neo-Gothic interpretation of furniture, whose features pointed to a place nearer heaven, Kimbel and Cabus were able to bring to American households a style that would give its members a firm moral basis in addition to an exciting new aesthetic.

With a fickle middle class that needed to keep up appearances, furnishings with greater refinement, lightness, and delicacy were quick to replace the massive, heavy, linear architectural style of the neo- Gothic that had swept the same population only a decade previous. By 1878 journals were already heralding Queen Anne style as the latest in home furnishings, a style that would foretell the decline of the Aesthetic Movement and firms like Kimbel & Cabus.

Preserving Kimbel and Cabus; or, The Trade Catalogue Itself

The Smithsonian Institution is the keeper of 6500 rare books at its New York library branch and is fortunate to have what some consider the only existing trade catalogue left from the business firm of Kimbel & Cabus. The remarkable documentary artifact, [Furniture Designed and Sold by the New York Firm of Kimbel & Cabus] , comprises the only visual record of their furniture and is the only evidence supporting the existence of the manufacturing firm to be found to date. The original 1870s catalogue, and a modern photographic reproduction of the 1870 catalogue (produced in 1976), are currently housed in the Cooper-Hewitt Museum Library’s rare book room and catalogued on Smithsonian Institution Libraries’ on-line catalogue, SIRIS, http://www.si.siris.edu/ . The original artifact was transferred to its current location at the Cooper-Hewitt when the library and collections of the Cooper Union Museum were moved in 1974.

The photo album contains images of approximately 184 furniture pieces that Kimbel & Cabus designed and manufactured in the 1870s (?). The catalogue reveals a diverse vocabulary which needs to be studied. Pieces in this catalogue include foliated ornament, large metal hinges, pointed arches and trefoil and quatrefoil patterns. A number of other pieces contain elements of the Modern Gothic style, characterized by elements such as ebonized wood with incised, gilded and linear ornament; tiled and painted panels on gold ground with medieval motifs; strapwork hinges and other elaborate hardware; turned wood galleries of spindles, hoof, trestle, or bracket feet; stiff-legged and rectilinear forms; and raised pediments with pointed arches.

In addition to the Modern Gothic, other pieces contain details and motifs inspired from a compendium of historic European and Asian patterns. Ottomans, inlaid work tables and cabinets with semi-circular arches are inspired from Middle Eastern and Moorish patterns while many of the upholstered armchairs, tête-à-têtes, and sofas, with floral motifs, curved forms, and plentiful fringes, are reminiscent of Second Empire style. Elaborate carved panels and ball feet are evidence of the influence of Elizabethan period furniture. Several pieces are adorned with Chinese- and Japanese-influenced details, notably faux bamboo woodwork, intricate oriental fretwork, and panels decorated with cranes, dragons, lions, and human figures in kimonos.

The catalogue illustrates the distinctive style of Kimbel & Cabus’s work where often the exaggerated sculptural forms, bold rectangular shapes, and decorative ornamentation have been emphasized over their functionality. In fact, the spectacularly ornamented and artistically designed pieces are constructed to be usable pieces of furniture. The range and style of their seating and casework could address the needs of prospective clients, possibly assisting customers in selecting designs to reflect their own needs and tastes – perhaps offering them a choice of a number of accessories or ornamental hardware, tiles or mirrors.

The catalogue contributes to the growing body of scholarship on the influence of the Aesthetic movement in furniture production at that time. It is currently used as a primary source for scholars and students of 19th century American decorative arts, especially the many who have already been consulting it since 1976, when the Cooper- Hewitt, National Design Museum Library opened its doors at the uptown landmark Andrew Carnegie Mansion. The catalogue is an essential resource for identifying actual pieces produced by Kimbel & Cabus in the 1870s -1880s. Without overstating its importance, the digitized trade catalogue offers continuous, reliable access to one of the only information sources about Kimbel & Cabus.

Up until now most if any scholarship has been a superficial gloss over Kimbel & Cabus, a nod of acknowledgement, but nothing much else, especially since we are left with no invoices, no business records, no letters. The fading studio photographs are believed to have been arranged as a practical sales tool, comprised solely of images and what appear to be some code numbers (which may be price codes). Although the numbers and codes have never been deciphered it is important that they be preserved so that further research may be conducted with this important, rare, and delightful glimpse into the world of 19th century New York cabinetmakers and New York Victorian interiors. The Kimbel & Cabus catalogue is also a picture album of the world of the Industrial Revolution – a time when engineering and aesthetics met for the first time, making and using everything from new textiles to springs for upholstered chairs.

Today the names Kimbel and Cabus most often bring to mind the terms neo-Gothic, Aesthetic movement, and Eastlake style, although the original trade catalogue shows a much more diverse inventory, one that included an impressive selection of furniture for every room of the home in styles that include Chinese and Japanese motifs, Moorish and Turkish influences, exotic textiles and Renaissance, Greek, Roman, and Egyptian Revival forms, as well. The original catalogue includes chairs, washstands, sofas, desks, settees, pedestals, revolving book stands, cabinets for -- dishes (cupboards), clothes (presses and armoires), music; wall shelves; dressing tables; buffets; sideboards, hat stands, easels, umbrella stands, many of which are displayed in suites or room arrangements. [INSERT EXAMPLE PHOTO].

Digitizing Kimbel & Cabus

The decision to extend the life of a particular artifact is especially thorny, necessarily limiting material access and providing instead a high-quality surrogate, but considering the level of cultural interest in the material, the trade book provided an ideal project. The digitization is expected to enhance interest in the material — material that can at best support a limited audience in terms of its condition.

Each image of the original catalogue from the 1870s has been scanned to provide access to each page of the trade catalogue, in thumbnail and oversized views, by browsing or by subject selection. The actual album, the paper artifact, will no longer be required for most scholarly work now.

This catalogue is one of the most important among the 6500 rare books in the Smithsonian’s New York collection, one that will continue to be in demand by researchers, staff, students, and others who will continue to use the collection. It cannot be replaced, only copied. The presence of the catalogue on the Internet gives access to the appropriate global audience now.

The web project will extend the life of the existing photographs of the catalogue by at least one hundred years, decreasing the use of the actual artifact to almost zero, and storing the “best possible images” on archival quality disks. The Smithsonian’s plans for long term retention include: [Stephen or Martin]

Technical Information

In accordance to the guidelines established by NARA and the Colorado Digitization Project, three versions of the images were created: a master image, an access image, and a thumbnail image (on server and CDs).

Images were scanned in greyscale at 600 dpi, using a flatbed Epson Expression 1600 scanner and including the Kodak standard grey patches in all scans. All images were scanned from a set of high-quality photographs made in 1976 from the original cards. Scanning the photographs avoids risk to the more fragile originals and also prevents twenty years of further deterioration of the cards. All images were inspected visually for quality assurance. Adobe Photoshop was used to produce smaller images for web display and indexing. Maxell Gold 700 MB CDs , MSM-A Color Therm, Archival quality disks were used to store a backup copy of the thumbnails.

Further Reading

Burke, Doreen Bolger, et. al. In pursuit of beauty : Americans and the Aesthetic Movement. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986.

Burrows, E.G. and Wallace, M. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Cook, Clarence. “Beds and tables, stools and candlesticks. X.” Scribner’s Monthly. April, 1877. vol. XIII, no. 6. pp. 816-820.

Downing, A.J. The Architecture of Country Houses. New York: Dover, 1969. (reprint)

Freeman, John C. Furniture for the Victorian home: from A.J. Downing (American): Country Houses (1850) and J.C. Loudon (English): encyclopedia (1833), 1968.

Gere, Charlotte. Nineteenth-century Decoration: The Art of the Interior. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1989.

Hanks, David. “Kimbel & Cabus: 19th-century New York Cabinetmakers.” New York: Art & Antiques, Sept-Oct 1980. pp. 44-53.

Howe, Katherine S., and David B. Warren. The Gothic Revival Style in America, 1830-1870. Exh. Cat. Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1976.

Meyer, Priscilla S. Victorian Detail: A Working Dictionary. Armonk, NY: Oak Cottage Farm. 1980.

Otto, Celia Jackson. American Furniture of the Nineteenth Century. New York: Viking Press, 1965.

Spofford, H. “Medieval furniture.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Vol. 54, Issue 318, Nov. 1876. pp. 809-830. [Illustrations on pages 825 and 828 are examples of Kimbel & Cabus, not Pottier & Stymus. Attribution corrected in Harper’s Vol. 54, Issue 319, Dec. 1876. p. 143.]

Talbert, Bruce J. Gothic Forms applied to furniture, metalwork and decoration for domestic purposes. London, 1868.

Voorsanger, Catherine Hoover, ed. “Gorgeous Articles of Furniture: Cabinetmaking in the Empire City,” in Art and The Empire City. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000. pp. 287-325.

Voorsanger, Catherine Hoover. “Kimbel and Cabus,” in Encyclopedia of Interior Design and Decoration. London; Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1997. pp. 675-677.

Wedgwood, A. Pugin Family Catalogue of the Drawings. Collection of the Royal Institute of British Architects, London: R.I.B.A., 1977.

[1] New York cabinetmakers like John Belter, Charles Baudouine, Alexander Roux

[2] Kimbel and Cabus may have purchased plaques and mounts from the firm, although no records exist to confirm this.

[3] Gothic Revival wavers between a folksy, decorated gingerbread style and a heavy linear medieval throwback.

[4] As you would expect, the terms also spelled “cabinetmaking” or “cabinet-making”, customarily consisted of two words in the nineteenth-century.

[5] “Ladies Mile” would become the name associated with women’s clothing and accessory stores proliferating along Broadway in Lower Manhattan in an area between 9th and 23rd Streets on Broadway and 6th Avenue (now also called Avenue of the Americas).

[6] Gothic Revival wavers between a folksy, decorated gingerbread style and a heavy linear medieval throwback.

[bey1]Hanks claims the date to be 1874.

Introduction

Anthony Kimbel and Joseph Cabus were names associated with fine cabinet making[1] in late nineteenth-century New York City where many other European-influenced firms also thrived in the industrious world of the furniture arts on Lower Broadway. Gustave and Christian Herter arrived in 1848. Edward W. Hutchings (1836-1856), Alexander Roux (1837-1881), Auguste Pottier (1823-1896) worked in the same neighborhood. The luxury hardware business of P.E. Guerin was founded on Jane Street in 1864.[2] While the names Kimbel and Cabus were spoken together in the same company as Herter and Roux, and they shared clientele with prominent architects like Stanford White, it is baffling that to date, other than a sole trade catalogue, ostensibly no invoices or other business records have been left behind. In spite of this, examples of Kimbel & Cabus furniture turn up in the Cooper-Hewitt, the Brooklyn Museum, the Hudson River Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and other public collections. There are also surviving examples in the US Capitol, Henry Ford Museum, and the High Museum of Art. Today Kimbel & Cabus are best remembered for having created and introduced the American version of Gothic Revival[3] style to a very receptive public at the Philadelphia Centennial in 1876.

Kimbel and Cabus [biographical details]

Between 1863 and 1882 in the Madison Square Park area of the City of New York, Anthony Kimbel and Joseph Cabus operated their fine cabinet making[4] ,decorating shop and showroom in the heart of the burgeoning retail district where R.H. Macy, B. Altman, and Lord & Taylor had already established themselves. [5] Their trade card read, “Kimbel and Cabus, Cabinet Makers and Decorators”, and paper labels with the same logo identified their wares.

Anthony Kimbel and Joseph Cabus moved many times during their close to twenty-year partnership, achieving some prosperity, but spent their peak years at 7 East 20th Street, and 458 10th Avenue. The firm achieved a reputation for high quality design and manufacture of furniture in a variety of styles, but gained prominence in the 1870s for developing an American version of Gothic Revival[6] or Modern Gothic style furniture featured in the trade catalogue dating from this period. [INSERT FIGURE]

Anthony Kimbel’s earliest training as a cabinet-maker was under the tutelage of his father Wilhelm (1786-1869), a master craftsman in Europe, and his godfather Anton Bembe (1799-1861), a furniture dealer and decorator in Mainz, Germany. He continued his education in Paris working with furniture maker Alexandre-Georges Fourdinois and publisher Desire Guilmard before coming to New York in 1847. In New York, Kimbel became the principal designer in the shop of Charles Baudouine and in 1854 established the firm of Kimbel & Bembe with the backing of his German uncle, Anton Bembe. Kimbel’s knowledge of European ornament and style (notably Rococo-Revival) and his ability to produce quality pieces for an American market enabled the firm of Kimbel & Bembe to flourish.

Joseph Cabus came from a family of French-born cabinet makers who had established a furniture manufacturing business in New York in the 1830s. As a boy, Joseph worked with his father Claude and then trained with the prominent cabinetmaker Alexander Roux in the 1850s before opening his own workshop at 924 Broadway, in 1862. Just a year later, Kimbel & Cabus would open, next door at 928. There in the years following the Civil War Kimbel & Cabus’s factory and showroom expanded greatly, allowing them to move to a quite fashionable site at 7& 9 East 20th Street by 1873[bey1] . In 1876, Kimbel and Cabus had developed a distinctive enough style of Modern Gothic at the Centennial in Philadelphia for their booth (#327) to be considered “rich and tasteful enough to rank among the very best of American exhibits in household art.” (Voorsanger, Encyclopedia of Interior Design). [INSERT FIGURE OF CENTENNIAL BOOTH]. At the height of their careers then, they were listed as exhibitors in the Official Catalogue of the 1876 International Exhibition in the Main Building’s Department of Manufactures with others — Brown & Bliss (#340), the Kilian Brothers (#338), Daniel Pabst (#361) , and Pottier & Stymus (#373), whose cabinets were similar in design to their own, and sometimes even mistaken for them.

Later commissions included the woodwork interiors and furniture for the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church (1875) and the interiors for a Company Room at the Seventh Avenue Regiment Armory (1879-1880). After Kimbel & Cabus closed their doors in 1882, both Anthony Kimbel and Joseph Cabus continued to work in partnership with their sons. A. Kimbel & Sons was more successful than Kimbel and Cabus and remained in business until 1941.

On his own, Joseph Cabus rose to prominence as a cabinet maker, but it was not until after the dissolution of the Kimbel and Cabus partnership that he landed his most famous commission in building the interior of the Church of the Ascension on lower Fifth Avenue in New York in collaboration with Stanford White in 1884.

Keeping Up Appearances: The new middle-class in late 19th century America

Victorian culture was the first to use the safety pin (1849), the typewriter (1867), the telephone (1875), and the first to profit from balloon frame construction (1832), a popular and inexpensive building technique that allowed people with modest incomes to afford to purchase homes. The mid- to late-nineteenth century in New York alone saw the rise of the first modern hotel (The Astor, 1830s), the first department store (A.T. Stewart Dry Goods, 1846), and the first chain grocery store (New York-based Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, 1864). Nearly six thousand newspapers and magazines were being published in the United States by 1870, with 1.5 million copies issued annually. A large percentage of these publications instructed the new middle class in etiquette, health, home decoration, gardening, hygiene, and taste. Its members developed a taste for the “new” as a way of “keeping up appearances,” which was not easy at a time when the most idiosyncratic and eclectic designs dominated the culture, especially the decorative arts. A young middle class was beginning to acquire decorative objects, the objects they saw at international fairs and in the lavishly illustrated magazines whose woodcuts they pored over. As long as the new middle class was able to imitate something that pleased their senses and be affiliated with the avant-garde, the demand for novelty would flourish. By 1877, Thorstein Veblen had coined the term conspicuous consumption to describe the drive to show off what you own to your friends and neighbors.

The furniture trades in New York City were thriving. Of the 4.2 million foreigners entering the United States between 1861 and 1877, most came ashore in New York City and would stay there. By 1870, New York was the busiest American seaport and the major distribution and sales center for imported goods in the country. At the same time, a number of skilled craftsmen and artisans arrived from Europe bringing with them both traditional and avant-garde designs which American firms quickly adopted, manufactured and marketed. The confluences of prosperity, technological and industrial innovation as well as the advent of mass merchandising provided opportunities for middle-class consumers to attain home ownership. These Victorians were the first ‘‘consumers” of mass-produced luxury items, made suddenly available to middle-class and wealthy households as one of the benefits of industrialization. As the economy expanded, the new middle class tastefully furnished their new residences with the latest styles and textiles of the day. Idiosyncratic and eclectic designs and products dominated the culture in the decorative arts.

The success of furniture manufacturing and interior furnishing firms such as Kimbel & Cabus was due to the patronage of this young, educated middle-class consumer who had developed a taste for the “new” as a way of “keeping up appearances.” New ideas and trends in etiquette, health, home decoration, gardening, hygiene, and taste, eagerly sought out by middle-class readers, became regular features in the nearly six-thousand newspapers and magazines being published in the United States by 1870. Illustrated serials and mail order catalogues fueled the desire to obtain fashionable decorative household objects as did the publication of a number of popular home decorating manuals. An abundance of popular magazines and manuals of instruction brought the great halls of the wealthy right to the parlors of the reading public. The Ladies Home Journal (first published in 1883), Cosmopolitan (1886) and Vogue (1892) raised the level of expectation for the burgeoning middle class.

How-to books like A.J. Downing’s The Architecture of Country Houses went through nine printings between 1850 and the end of the Civil War. Downing’s choice of furnishings for his audience did much to prescribe the types of furnishings that the new homeowner should choose in establishing an ideal American way of life and emphasizing the practice of attaining prestige. He did much to establish the understanding of the picturesque as beautiful and the unity of design as a form of truth and high morals. In the history of taste, it must be considered one of the nineteenth century’s best “how-to” manuals as well as a primer of the aesthetic interior and its accompanying manners and values.

The opportunity to own a home became affordable with the rise of mass culture, and with the rage for home ownership and the proliferation of the middle classes, the stage was set for craftsmen to sell their wares to a new market. The Victorians were the first “customers” of mass industry, and they wanted whatever elevated their status. The home was the ideal place to display status. The neo-Gothic with its underlying accent on perfection was just the right line of products to pitch to the first mass consumers, who yearned to have the pleasures of the wealthy. With their linearity and pointed features, Kimbel & Cabus’s furnishings offered the connection between the Gothic and good character that Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin established in England through writings that influenced Bruce Talbert and others. With their neo-Gothic interpretation of furniture, whose features pointed to a place nearer heaven, Kimbel and Cabus were able to bring to American households a style that would give its members a firm moral basis in addition to an exciting new aesthetic.

With a fickle middle class that needed to keep up appearances, furnishings with greater refinement, lightness, and delicacy were quick to replace the massive, heavy, linear architectural style of the neo- Gothic that had swept the same population only a decade previous. By 1878 journals were already heralding Queen Anne style as the latest in home furnishings, a style that would foretell the decline of the Aesthetic Movement and firms like Kimbel & Cabus.

Preserving Kimbel and Cabus; or, The Trade Catalogue Itself

The Smithsonian Institution is the keeper of 6500 rare books at its New York library branch and is fortunate to have what some consider the only existing trade catalogue left from the business firm of Kimbel & Cabus. The remarkable documentary artifact, [Furniture Designed and Sold by the New York Firm of Kimbel & Cabus] , comprises the only visual record of their furniture and is the only evidence supporting the existence of the manufacturing firm to be found to date. The original 1870s catalogue, and a modern photographic reproduction of the 1870 catalogue (produced in 1976), are currently housed in the Cooper-Hewitt Museum Library’s rare book room and catalogued on Smithsonian Institution Libraries’ on-line catalogue, SIRIS, http://www.si.siris.edu/ . The original artifact was transferred to its current location at the Cooper-Hewitt when the library and collections of the Cooper Union Museum were moved in 1974.

The photo album contains images of approximately 184 furniture pieces that Kimbel & Cabus designed and manufactured in the 1870s (?). The catalogue reveals a diverse vocabulary which needs to be studied. Pieces in this catalogue include foliated ornament, large metal hinges, pointed arches and trefoil and quatrefoil patterns. A number of other pieces contain elements of the Modern Gothic style, characterized by elements such as ebonized wood with incised, gilded and linear ornament; tiled and painted panels on gold ground with medieval motifs; strapwork hinges and other elaborate hardware; turned wood galleries of spindles, hoof, trestle, or bracket feet; stiff-legged and rectilinear forms; and raised pediments with pointed arches.

In addition to the Modern Gothic, other pieces contain details and motifs inspired from a compendium of historic European and Asian patterns. Ottomans, inlaid work tables and cabinets with semi-circular arches are inspired from Middle Eastern and Moorish patterns while many of the upholstered armchairs, tête-à-têtes, and sofas, with floral motifs, curved forms, and plentiful fringes, are reminiscent of Second Empire style. Elaborate carved panels and ball feet are evidence of the influence of Elizabethan period furniture. Several pieces are adorned with Chinese- and Japanese-influenced details, notably faux bamboo woodwork, intricate oriental fretwork, and panels decorated with cranes, dragons, lions, and human figures in kimonos.

The catalogue illustrates the distinctive style of Kimbel & Cabus’s work where often the exaggerated sculptural forms, bold rectangular shapes, and decorative ornamentation have been emphasized over their functionality. In fact, the spectacularly ornamented and artistically designed pieces are constructed to be usable pieces of furniture. The range and style of their seating and casework could address the needs of prospective clients, possibly assisting customers in selecting designs to reflect their own needs and tastes – perhaps offering them a choice of a number of accessories or ornamental hardware, tiles or mirrors.

The catalogue contributes to the growing body of scholarship on the influence of the Aesthetic movement in furniture production at that time. It is currently used as a primary source for scholars and students of 19th century American decorative arts, especially the many who have already been consulting it since 1976, when the Cooper- Hewitt, National Design Museum Library opened its doors at the uptown landmark Andrew Carnegie Mansion. The catalogue is an essential resource for identifying actual pieces produced by Kimbel & Cabus in the 1870s -1880s. Without overstating its importance, the digitized trade catalogue offers continuous, reliable access to one of the only information sources about Kimbel & Cabus.

Up until now most if any scholarship has been a superficial gloss over Kimbel & Cabus, a nod of acknowledgement, but nothing much else, especially since we are left with no invoices, no business records, no letters. The fading studio photographs are believed to have been arranged as a practical sales tool, comprised solely of images and what appear to be some code numbers (which may be price codes). Although the numbers and codes have never been deciphered it is important that they be preserved so that further research may be conducted with this important, rare, and delightful glimpse into the world of 19th century New York cabinetmakers and New York Victorian interiors. The Kimbel & Cabus catalogue is also a picture album of the world of the Industrial Revolution – a time when engineering and aesthetics met for the first time, making and using everything from new textiles to springs for upholstered chairs.

Today the names Kimbel and Cabus most often bring to mind the terms neo-Gothic, Aesthetic movement, and Eastlake style, although the original trade catalogue shows a much more diverse inventory, one that included an impressive selection of furniture for every room of the home in styles that include Chinese and Japanese motifs, Moorish and Turkish influences, exotic textiles and Renaissance, Greek, Roman, and Egyptian Revival forms, as well. The original catalogue includes chairs, washstands, sofas, desks, settees, pedestals, revolving book stands, cabinets for -- dishes (cupboards), clothes (presses and armoires), music; wall shelves; dressing tables; buffets; sideboards, hat stands, easels, umbrella stands, many of which are displayed in suites or room arrangements. [INSERT EXAMPLE PHOTO].

Digitizing Kimbel & Cabus

The decision to extend the life of a particular artifact is especially thorny, necessarily limiting material access and providing instead a high-quality surrogate, but considering the level of cultural interest in the material, the trade book provided an ideal project. The digitization is expected to enhance interest in the material — material that can at best support a limited audience in terms of its condition.

Each image of the original catalogue from the 1870s has been scanned to provide access to each page of the trade catalogue, in thumbnail and oversized views, by browsing or by subject selection. The actual album, the paper artifact, will no longer be required for most scholarly work now.

This catalogue is one of the most important among the 6500 rare books in the Smithsonian’s New York collection, one that will continue to be in demand by researchers, staff, students, and others who will continue to use the collection. It cannot be replaced, only copied. The presence of the catalogue on the Internet gives access to the appropriate global audience now.

The web project will extend the life of the existing photographs of the catalogue by at least one hundred years, decreasing the use of the actual artifact to almost zero, and storing the “best possible images” on archival quality disks. The Smithsonian’s plans for long term retention include: [Stephen or Martin]

Technical Information

In accordance to the guidelines established by NARA and the Colorado Digitization Project, three versions of the images were created: a master image, an access image, and a thumbnail image (on server and CDs).

Images were scanned in greyscale at 600 dpi, using a flatbed Epson Expression 1600 scanner and including the Kodak standard grey patches in all scans. All images were scanned from a set of high-quality photographs made in 1976 from the original cards. Scanning the photographs avoids risk to the more fragile originals and also prevents twenty years of further deterioration of the cards. All images were inspected visually for quality assurance. Adobe Photoshop was used to produce smaller images for web display and indexing. Maxell Gold 700 MB CDs , MSM-A Color Therm, Archival quality disks were used to store a backup copy of the thumbnails.

Further Reading

Burke, Doreen Bolger, et. al. In pursuit of beauty : Americans and the Aesthetic Movement. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986.

Burrows, E.G. and Wallace, M. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Cook, Clarence. “Beds and tables, stools and candlesticks. X.” Scribner’s Monthly. April, 1877. vol. XIII, no. 6. pp. 816-820.

Downing, A.J. The Architecture of Country Houses. New York: Dover, 1969. (reprint)

Freeman, John C. Furniture for the Victorian home: from A.J. Downing (American): Country Houses (1850) and J.C. Loudon (English): encyclopedia (1833), 1968.

Gere, Charlotte. Nineteenth-century Decoration: The Art of the Interior. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1989.

Hanks, David. “Kimbel & Cabus: 19th-century New York Cabinetmakers.” New York: Art & Antiques, Sept-Oct 1980. pp. 44-53.

Howe, Katherine S., and David B. Warren. The Gothic Revival Style in America, 1830-1870. Exh. Cat. Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1976.

Meyer, Priscilla S. Victorian Detail: A Working Dictionary. Armonk, NY: Oak Cottage Farm. 1980.

Otto, Celia Jackson. American Furniture of the Nineteenth Century. New York: Viking Press, 1965.

Spofford, H. “Medieval furniture.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Vol. 54, Issue 318, Nov. 1876. pp. 809-830. [Illustrations on pages 825 and 828 are examples of Kimbel & Cabus, not Pottier & Stymus. Attribution corrected in Harper’s Vol. 54, Issue 319, Dec. 1876. p. 143.]

Talbert, Bruce J. Gothic Forms applied to furniture, metalwork and decoration for domestic purposes. London, 1868.

Voorsanger, Catherine Hoover, ed. “Gorgeous Articles of Furniture: Cabinetmaking in the Empire City,” in Art and The Empire City. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000. pp. 287-325.

Voorsanger, Catherine Hoover. “Kimbel and Cabus,” in Encyclopedia of Interior Design and Decoration. London; Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1997. pp. 675-677.

Wedgwood, A. Pugin Family Catalogue of the Drawings. Collection of the Royal Institute of British Architects, London: R.I.B.A., 1977.

[1] New York cabinetmakers like John Belter, Charles Baudouine, Alexander Roux

[2] Kimbel and Cabus may have purchased plaques and mounts from the firm, although no records exist to confirm this.

[3] Gothic Revival wavers between a folksy, decorated gingerbread style and a heavy linear medieval throwback.

[4] As you would expect, the terms also spelled “cabinetmaking” or “cabinet-making”, customarily consisted of two words in the nineteenth-century.

[5] “Ladies Mile” would become the name associated with women’s clothing and accessory stores proliferating along Broadway in Lower Manhattan in an area between 9th and 23rd Streets on Broadway and 6th Avenue (now also called Avenue of the Americas).

[6] Gothic Revival wavers between a folksy, decorated gingerbread style and a heavy linear medieval throwback.

[bey1]Hanks claims the date to be 1874.

Sunday, July 15, 2007

Return to New York; From this valley (valet) they say you are leaving

After a harrowing six weeks in the Connecticut River Valley to work on a cataloging project, I return with a better than average chance of restoring my faith in the integrity of librarianship.

Tuesday, August 29, 2006

DADA and library theory

there is much to be gained by realizing that library literature offers many charts which offer no illustration of the text they are supposed to explain or clarify. by their very nature, charts are in form at least supposed to explain. after visiting the traveling dada exhibit recently at moma i decided that schwitters's collages offer far more in the way of elucidation than the figures and diagrams that appeared in their embarrassingly small 4 to 6 point fonts throughout library literature. much more will be written about the manifestos of library theory some other time. after all, i am in search of my own place in librarianship. swamped by lots of information. i must sort through thousands if not hundreds of thousands of characters every day. dayenu. tomorrow i continue reading in hebrew. my wednesday grounding.

Friday, April 28, 2006

Bookselling This Week: The Book Sense 2006 - 2007 Reading Group Picks

One of the most useful lists for book lovers came out recently. Come here to see it anytime. Bookselling This Week: The Book Sense 2006 - 2007 Reading Group Picks

Thursday, April 06, 2006

"Feed Me, Seymour," or the confusion of RSS

Why does everyone think syndication (RSS by any other name??) is so simple to understand and install? The confusion begins with the choices. How many companies are offering RSS, and what are their differences? After you choose one, how do you remember how or where you installed it -- just in case you change your mind.

RSS looks like hypertext but it seems to have a really important function -- you can get the latest "feed" to the latest news from wherevever you choose, say, Moldova, if you connect to an information source that links to that information.

Next time, the cosmotechnicomical names of your sources.

RSS looks like hypertext but it seems to have a really important function -- you can get the latest "feed" to the latest news from wherevever you choose, say, Moldova, if you connect to an information source that links to that information.

Next time, the cosmotechnicomical names of your sources.

Monday, May 02, 2005

Last(ing) Thoughts about Human Information Behavior as a Science

Human information behavior is young and its curious newness has attracted those in education, information science, information technology, library science and the social sciences, some with great fervor. No voice has been more dominant in theorizing with some of its clever acronyms and its pseudo-scientific social observations.

Take a look at some of the diagrams and some of the charts and some of the measurements. This is definitely the softest of sciences and it uses the oldest of scientific instruments, human observation.

But human observation is at best, unreliable, so how can a “science” today be built on “human observation” as HIB continues to be?

Libraries today struggle with painting their walls and filling their shelves, except when it comes to videos and DVDs. We have become a more visual culture in the last 30 years. This coincides with a decline in reading skills. Are libraries still catering to a public that no longer exists, or are the functions of the library evolving to continue to meet the needs of their individual charters?

The library is at a crossroads between being a building and being a service. Human information behavior is studying the patterns that determine its institutional future. If human information behavior is performing a vital function in understanding the ways people seek information and that activity is vital and constant, then the knowledge coming from the studies could be applied to schools and libraries policies. With an adequate budget, any information source can survive, if it understands its constituencies, and principles of marketing.

Take a look at some of the diagrams and some of the charts and some of the measurements. This is definitely the softest of sciences and it uses the oldest of scientific instruments, human observation.

But human observation is at best, unreliable, so how can a “science” today be built on “human observation” as HIB continues to be?

Libraries today struggle with painting their walls and filling their shelves, except when it comes to videos and DVDs. We have become a more visual culture in the last 30 years. This coincides with a decline in reading skills. Are libraries still catering to a public that no longer exists, or are the functions of the library evolving to continue to meet the needs of their individual charters?

The library is at a crossroads between being a building and being a service. Human information behavior is studying the patterns that determine its institutional future. If human information behavior is performing a vital function in understanding the ways people seek information and that activity is vital and constant, then the knowledge coming from the studies could be applied to schools and libraries policies. With an adequate budget, any information source can survive, if it understands its constituencies, and principles of marketing.

Mrs. Morrow Stimulated the Soup

Brown, J.S., Collins, A., and Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, Jan/Feb, 32-42.

It is really no relief that Alfred North Whitehead wrote The Aims of Education almost 80 years ago, and there is still an almost criminal amount of useless knowledge being passed on from teacher to student from year to year. Why haven’t we learned that decontextualized learning just doesn’t stick? And if we have learned that, especially as information specialists (an offensive term, I think) we either believe that all of the theoretical concepts we have read and written about will suddenly become clear, or connected to some experience, or even become useful. But, then again, probably not. The curriculum goes on teaching abstract concepts as self-sufficient things, like carrots.

Knowing and doing cannot be separated. Its corollary also makes sense: using the tools of a profession without being inside the culture makes no sense.

The language is a tool, and learning it is a natural process. The best way is immersion. Jonathan Safran Foer’s Everything is Illuminated has some of the best examples of language learned directly from a dictionary rather than social experience. In other words, language is totally context-dependent. The article is built on the central metaphor that all tools are like language, and are acquired through situated use and practice.

How can classroom activity approach authentic activity? How can library practice approach authentic activity?

As long as there is education there will be education reform, and this article points to the lethargy of a system that does not work but has been situated for a long time.

It is really no relief that Alfred North Whitehead wrote The Aims of Education almost 80 years ago, and there is still an almost criminal amount of useless knowledge being passed on from teacher to student from year to year. Why haven’t we learned that decontextualized learning just doesn’t stick? And if we have learned that, especially as information specialists (an offensive term, I think) we either believe that all of the theoretical concepts we have read and written about will suddenly become clear, or connected to some experience, or even become useful. But, then again, probably not. The curriculum goes on teaching abstract concepts as self-sufficient things, like carrots.

Knowing and doing cannot be separated. Its corollary also makes sense: using the tools of a profession without being inside the culture makes no sense.

The language is a tool, and learning it is a natural process. The best way is immersion. Jonathan Safran Foer’s Everything is Illuminated has some of the best examples of language learned directly from a dictionary rather than social experience. In other words, language is totally context-dependent. The article is built on the central metaphor that all tools are like language, and are acquired through situated use and practice.

How can classroom activity approach authentic activity? How can library practice approach authentic activity?

As long as there is education there will be education reform, and this article points to the lethargy of a system that does not work but has been situated for a long time.

Thursday, April 28, 2005

Affective Aspects of the Information Search

Kulthau, C. (1991). Inside the search process: information seeking from the user’s perspective. JASIS. 42(5):361-371.

In the early 1990s Kulthau was involved in articulating the stages of the information seeking process from the user’s perspective. The researchers in human information behavior rally around any theory that places the user at the center of the information universe.

Kulthau extends the meaning of John Seely Brown’s situated cognition theories which focus on the culture of learning as either useless or meaningful, that is, either effective or ineffective. Kulthau, as an educator, understands the integration of knowledge or search results into the user’s own life. She extends Dervin’s sense-making theories, and builds on Belkin’s ASK model.

It is significant for students or any users of information to realize that the process of research involves more than the search for sources, but is a transformation in what the user knows. If what the user finds out does not coincide with what the user already knows, then what happens? Uncertainty or confusion.

In the early 1990s Kulthau was involved in articulating the stages of the information seeking process from the user’s perspective. The researchers in human information behavior rally around any theory that places the user at the center of the information universe.

Kulthau extends the meaning of John Seely Brown’s situated cognition theories which focus on the culture of learning as either useless or meaningful, that is, either effective or ineffective. Kulthau, as an educator, understands the integration of knowledge or search results into the user’s own life. She extends Dervin’s sense-making theories, and builds on Belkin’s ASK model.

It is significant for students or any users of information to realize that the process of research involves more than the search for sources, but is a transformation in what the user knows. If what the user finds out does not coincide with what the user already knows, then what happens? Uncertainty or confusion.

Tuesday, April 19, 2005

Art historians and secrecy

There are two theorists whose ideas make the most sense in relation to the way art historians work as practitioners: Kulthau, and Duguid. Situated cognition is especially relevant to the understanding of art historians, as is the culture of learning as examined by John Seely Brown and Paul Duguid. The aspect of sharing knowledge is a theme that needs to be explored. Even though art historians rely on colleagues for information and admit to being members of an invisibile college, they find it very important to gather information first-hand, and above all, claim their territory. The ultimate effect of these customs is that knowledge is held up for the most part, while other scholars step aside for works-in-progress which are simply gathering dust after an announcement of their beginnings, say, 10 - 15 years ago. Outrageous.

The apprenticeship of the art historian soon leads to connoisseurship.

The apprenticeship of the art historian soon leads to connoisseurship.

Discursive Action from Wittgenstein to Kulthau

Kulthau, Carol C. (1991). Inside the search process: information seeking from the user’s perspective, Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42(5), 361-371. John Wiley and Sons Inc.

You can only procrastinate for so long before it’s time to take care of work. what did I do in my last lifetime to deserve to read articles like this? actually, that comment doesn’t apply that readily to kulthau's article. Kulthau was one of the pioneers in info seeking behavior by looking at affective and cognitive states and conducting empirical research. She looked at a variety of groups over a long period of time (longitudinal studies). thesis is qauite relevant for 1991. more than 10 years ago. studying user behavior wasn’t even a thought then. at least not from a social vantage point. I don’t get the social thing. I’ve always come from a rather personal and psychological model, so getting the social message hasn’t quite sunk in. I know a journal that is being looked at by someone else is a changed journal, not truly reflecting what I would say. like, this stinks. having to read social science articles with bad drawings that illustrate nothing. well, this really has more to do with other articles. now, on to carol kulthau. she is trying to find a new model to study information seeking. is aware of dervin’s research which preceded hers (1983), and agrees with dervin in that once a person can make meaningn or “make sense” of information or a task, then it’s all downhill from there. things will flow. but before that there is anxiety. and it’s ok, she assures us. the solution to a problem will be shared (109). kulthau derives her model from a series of five studies in info seeking behavior, and stresses that what a user feels and thinks during the early stages is important to pay attention to, and studies have not paid that any heed. kulthau points to further studies and urges further research based upon the groundbreaking she has done.

problems with systems based approach is tht the system doesn’t recognize different stages of information seeking, and will offer the same limited options to find an answer, which requires a more focused frame of mind than a user has in the beginning of a search. kulthau feels that her approach is unique in that it goes beyond the cognitive to examine the affective – the feelings that users commonly have when in a very early stage of exploration. uncertainty and anxiety must be addressed in system design and the reference interview. kulthau examines the users’ perspective of information seeking, and she does that by paying attention to what the user is feeling. a wonderful point is made about the discursive nature of information in that the user will have arrived and feel relieved when a personal perspective is found. kulthau compares five different theoretical foundations for ISP: phases of construction (Kelly), levels of need (Taylor), levels of specificity (Belkin), expression (Belkin, Taylor) and mood (Kelly). The five theories rest on a change in users’ feelings whether they be changes in thoughts which can alter the specificity of the need and its expression, feelings, or mood. kulthau feels that it may be more difficult to study thoughts and feelings, but it is the only way to find more out about information seeking behavior. by the way, what is the difference between affective feelings and feelings? can affective feelings be observed by someone else or must they be expressed by the user? sometimes we are not even sure what we feel, so even feelings are blurry.

increases in confidence corresponds to an increase in clarity and focus. but is kulthau talking about cause and effect, or a correlation that goes both ways? as we make more sense, we get better grades. god, this is so circular, as with most of the articles. but actually, I like kulthau, as she patiently moves from smaller and shorter studies and when the theory holds, moves to larger and longer studies. good research. looking at a small sample and then testing at a more significant level. info seekers go through three stages: at first seeking background information, then at midpoint seeking general information, and then moving in for the closure with specific questions, and the ability to make focused statements. the user changes throughout the process. the process is also looked at as a series of tasks in TABLE 3, in summary, moving from gathering to gathering/completing and then finally to writing or presenting. kulthau shares the view with many others that you must nurture the info seeking process, not writing too soon, not expecting ideas to be well-formed at the beginning. I feel that writing and thinking influence each other and that if you are willing to face your unformed and somewhat irrational thoughts, if you are willing to put them on paper, they will change what you know, and help you to construct meaning. kulthau’s theories are not unique. writing instructors urge their students to write in journals to learn discursively.

Tuominen, Kimmo and Savolainen, Reijo. A social constructionist approach to the study of information use as discursive action,

Definition and influential texts:

Most interesting article to date and needs more investigation. Text in conversation with the reader is probably the most interesting thing we have read to date. Talking through our artifacts. Many things in common with Dervin and Nilan who stress that the personal subjective is most important. Kulthau also stresses the importance of integrating information into a personal viewpoint. The text is simply a starting point. Have to trace some of the footnotes. Social constructionism dates back to Berger and Luckmann’s 1966 work “the social construction of reality” but since then other theories have influences it, namely poststructuralist thinking (Foucault), linguistic philosophy (Austin and Wittgenstein), etc. they are all included in Tuominen and Savolainen’s article. Social constructivism has influenced other disciplines such

as literary criticism and authors believe that socially and dialogically oriented research approaches will gain popularity in information studies. and they have already. the studies taking place now take into account the conversations going on with the text. or the interface the authors believe that. Dervin’s approach “communitarianism” comes very close to “constructionism.”

Other influences have appeared, namely (forget it, not enough time to mention, but I’ll return to the text later). Besides, this journal is for my benefit, and its map may not be clear to others but it is a discursive tool. I think here. A study of information use through the methodology of constructionism, based heavily in theory that no one ever understood anyway. Subjective approach. What is discourse? Talk and writing. interaction with text. everything is text. text is information. we can converse with anything. we change the text by discourse. this view stands in opposition to cognitive approach which dominated user studies until the 1970s. This article is also about making sense, i.e. the active role we take in interpreting texts and changing them through our interpretation. Too bad my critical viewpoint grew out of a McLuhanesque and Jungian perspective with little post-modern inclination. That was happening in Irvine, California and Paris. I thought that people realized that post-modern thought was a joke. That it was all for fun. Now, library science and

IT practitioners embrace it. That brings us to Umberto Eco and Travels in Hyperreality, something I have to study on my own. But Tuominen and Savolainen introduce us to social constructionism and its definitions:

language is not an abstract system disconnected from talking and writing. the human being is not the point of departure. the most important things take place in discursive interaction. knowledge is something people do together, not something that one person possesses. so I guess they’re talking about a cultural storehouse to which we each contribute, but we could not contribute if we did not build upon what others have shared with us. Is that it? there are amazing applications to the internet and the commons. the conduit between us – the networks and the online communities. oh, this has got to be hype.

authors build upon the making sense model of Dervin (1991)

Who is Jerome Bruner and the Cognitive Revolution. Let’s take a peek at the references. H-m-m-m—m-m—m-m. Acts of Meaning (1990). I’ll take it out of the library if they have it. So far I like the observation, “cognitive science employing the computer analogy has gravitated toward technical and culturally insignificant questions.” Yes. because according to the authors the analysis of social and cultural meaning is stifled through the analogy.

context is paramount.

authors defend their discursive methodology.

methods of description

influences: Wittgenstein, etc.

You can only procrastinate for so long before it’s time to take care of work. what did I do in my last lifetime to deserve to read articles like this? actually, that comment doesn’t apply that readily to kulthau's article. Kulthau was one of the pioneers in info seeking behavior by looking at affective and cognitive states and conducting empirical research. She looked at a variety of groups over a long period of time (longitudinal studies). thesis is qauite relevant for 1991. more than 10 years ago. studying user behavior wasn’t even a thought then. at least not from a social vantage point. I don’t get the social thing. I’ve always come from a rather personal and psychological model, so getting the social message hasn’t quite sunk in. I know a journal that is being looked at by someone else is a changed journal, not truly reflecting what I would say. like, this stinks. having to read social science articles with bad drawings that illustrate nothing. well, this really has more to do with other articles. now, on to carol kulthau. she is trying to find a new model to study information seeking. is aware of dervin’s research which preceded hers (1983), and agrees with dervin in that once a person can make meaningn or “make sense” of information or a task, then it’s all downhill from there. things will flow. but before that there is anxiety. and it’s ok, she assures us. the solution to a problem will be shared (109). kulthau derives her model from a series of five studies in info seeking behavior, and stresses that what a user feels and thinks during the early stages is important to pay attention to, and studies have not paid that any heed. kulthau points to further studies and urges further research based upon the groundbreaking she has done.

problems with systems based approach is tht the system doesn’t recognize different stages of information seeking, and will offer the same limited options to find an answer, which requires a more focused frame of mind than a user has in the beginning of a search. kulthau feels that her approach is unique in that it goes beyond the cognitive to examine the affective – the feelings that users commonly have when in a very early stage of exploration. uncertainty and anxiety must be addressed in system design and the reference interview. kulthau examines the users’ perspective of information seeking, and she does that by paying attention to what the user is feeling. a wonderful point is made about the discursive nature of information in that the user will have arrived and feel relieved when a personal perspective is found. kulthau compares five different theoretical foundations for ISP: phases of construction (Kelly), levels of need (Taylor), levels of specificity (Belkin), expression (Belkin, Taylor) and mood (Kelly). The five theories rest on a change in users’ feelings whether they be changes in thoughts which can alter the specificity of the need and its expression, feelings, or mood. kulthau feels that it may be more difficult to study thoughts and feelings, but it is the only way to find more out about information seeking behavior. by the way, what is the difference between affective feelings and feelings? can affective feelings be observed by someone else or must they be expressed by the user? sometimes we are not even sure what we feel, so even feelings are blurry.

increases in confidence corresponds to an increase in clarity and focus. but is kulthau talking about cause and effect, or a correlation that goes both ways? as we make more sense, we get better grades. god, this is so circular, as with most of the articles. but actually, I like kulthau, as she patiently moves from smaller and shorter studies and when the theory holds, moves to larger and longer studies. good research. looking at a small sample and then testing at a more significant level. info seekers go through three stages: at first seeking background information, then at midpoint seeking general information, and then moving in for the closure with specific questions, and the ability to make focused statements. the user changes throughout the process. the process is also looked at as a series of tasks in TABLE 3, in summary, moving from gathering to gathering/completing and then finally to writing or presenting. kulthau shares the view with many others that you must nurture the info seeking process, not writing too soon, not expecting ideas to be well-formed at the beginning. I feel that writing and thinking influence each other and that if you are willing to face your unformed and somewhat irrational thoughts, if you are willing to put them on paper, they will change what you know, and help you to construct meaning. kulthau’s theories are not unique. writing instructors urge their students to write in journals to learn discursively.

Tuominen, Kimmo and Savolainen, Reijo. A social constructionist approach to the study of information use as discursive action,

Definition and influential texts:

Most interesting article to date and needs more investigation. Text in conversation with the reader is probably the most interesting thing we have read to date. Talking through our artifacts. Many things in common with Dervin and Nilan who stress that the personal subjective is most important. Kulthau also stresses the importance of integrating information into a personal viewpoint. The text is simply a starting point. Have to trace some of the footnotes. Social constructionism dates back to Berger and Luckmann’s 1966 work “the social construction of reality” but since then other theories have influences it, namely poststructuralist thinking (Foucault), linguistic philosophy (Austin and Wittgenstein), etc. they are all included in Tuominen and Savolainen’s article. Social constructivism has influenced other disciplines such

as literary criticism and authors believe that socially and dialogically oriented research approaches will gain popularity in information studies. and they have already. the studies taking place now take into account the conversations going on with the text. or the interface the authors believe that. Dervin’s approach “communitarianism” comes very close to “constructionism.”

Other influences have appeared, namely (forget it, not enough time to mention, but I’ll return to the text later). Besides, this journal is for my benefit, and its map may not be clear to others but it is a discursive tool. I think here. A study of information use through the methodology of constructionism, based heavily in theory that no one ever understood anyway. Subjective approach. What is discourse? Talk and writing. interaction with text. everything is text. text is information. we can converse with anything. we change the text by discourse. this view stands in opposition to cognitive approach which dominated user studies until the 1970s. This article is also about making sense, i.e. the active role we take in interpreting texts and changing them through our interpretation. Too bad my critical viewpoint grew out of a McLuhanesque and Jungian perspective with little post-modern inclination. That was happening in Irvine, California and Paris. I thought that people realized that post-modern thought was a joke. That it was all for fun. Now, library science and

IT practitioners embrace it. That brings us to Umberto Eco and Travels in Hyperreality, something I have to study on my own. But Tuominen and Savolainen introduce us to social constructionism and its definitions:

language is not an abstract system disconnected from talking and writing. the human being is not the point of departure. the most important things take place in discursive interaction. knowledge is something people do together, not something that one person possesses. so I guess they’re talking about a cultural storehouse to which we each contribute, but we could not contribute if we did not build upon what others have shared with us. Is that it? there are amazing applications to the internet and the commons. the conduit between us – the networks and the online communities. oh, this has got to be hype.

authors build upon the making sense model of Dervin (1991)

Who is Jerome Bruner and the Cognitive Revolution. Let’s take a peek at the references. H-m-m-m—m-m—m-m. Acts of Meaning (1990). I’ll take it out of the library if they have it. So far I like the observation, “cognitive science employing the computer analogy has gravitated toward technical and culturally insignificant questions.” Yes. because according to the authors the analysis of social and cultural meaning is stifled through the analogy.

context is paramount.

authors defend their discursive methodology.

methods of description

influences: Wittgenstein, etc.

Sunday, April 17, 2005

Real Questions, Real Needs

Dewdney, P. and Michell, G. (1997). Asking “why” questions in the reference interview: a theoretical justification. Library Quarterly 67(1), 50-71.

The sincerity of asking “why” on the part of librarians is generally misunderstood by patrons/information seekers. Patricia Dewdney and Gillian Michell return to visit an area rich in conflict and ripe for conflict resolution: the reference interview. A librarian’s best effort to figure out a patron’s motives may be misunderstood as intrusive, and responded to in a hostile manner. The authors apply two strategies to make “why” successful in a reference interview, contextualization and neutral questioning, relying on theory in “philosophy, linguistics, cognitive science, and communications” (51) to support their arguments, but are concerned with earlier work by Hutchins (1944), R. Taylor (1968).

Obviously, the well-known grouchiness of librarians has been around ever since the first reference question interrupted a librarian completing the Sunday New York Times crossword puzzle. The librarian would naturally wonder “why” anyone would care to ruin another day in [her] life by asking [her] anything. Obviously, Robert Taylor and Nick Belkin and many others have stressed the importance of knowing why in order to know what a patron “really” wants to know. This topic first became relevant with Robert Taylor’s 1968 article on negotiating questions, and has pushed the human information behavior researcher’s pen to the paper for the past 40 years or so.Dewdney and Michell, although theorists, come up with some practical answers, albeit their responses to resolving the troublesome nature of “why” really takes much practice. First of all, librarians must be more sensitive to what is being conveyed by their questions. Speech act theory gives some insight into what philosophers and linguists rely on to determine the nature of communication between the librarian and the information seeker. Simple questions of fact can be confused with a request for more information. The “why” question also opens up other territory, some of which is not very comfortable for the librarian, like when the patron’s answer to the sweet and sincere librarian’s “Why are you asking me for this information?” gets a “None of your business” in reply. Theoretical considerations provide all the support for the authors as promised, although Dewdney obviously put in her field time training reference librarians prior to the publication of her dissertation in 1986 on the topic. The research interview obviously is not an easy one to conduct, regardless of what the question is, especially when even a ready reference question may have a hidden motive. The authors’ practical snippets of dialogue make the arguments clear, but for the reader, they are only the beginning of becoming a skilled reference interviewer. The reader must agree with the authors that a philosophical basis must be at the foundation of training reference workers. Without knowing the theoretical basis for actions, librarians will continue to misunderstand their patrons, and vice versa. A number of early source works from the article seem interesting in the light of what we think of as the first 50 years or so of human information behavior.